Have you ever stopped to wonder about the sounds that echoed through the very first human settlements, long before written history began? It's a fascinating thought, isn't it? We often think of music as a modern comfort, yet the human connection to rhythm and melody runs incredibly deep. So, the idea of finding the very first song ever created really captures the imagination.

This quest for the earliest known tune is, in some respects, a bit like searching for the first spoken word or the first drawing on a cave wall. It connects us directly to the ancient minds that shaped our world. We're talking about sounds that might have accompanied rituals, celebrated victories, or soothed sorrows in times we can barely imagine. That, you know, is a pretty profound link to the past.

Trying to pinpoint the absolute oldest song is a challenge, though, because music, particularly in its earliest forms, was often passed down orally. It didn't always leave behind a clear, written record for us to discover thousands of years later. This makes the job of archaeologists and music historians a rather tricky one, as a matter of fact.

Table of Contents

- The Elusive Quest for the Oldest Song

- What Even Counts as a "Song"?

- Early Musical Instruments: The Precursors

- The Dawn of Notation: A Glimmer of Hope

- The Hurrian Hymn No. 6: A Strong Contender

- Interpreting Ancient Sounds: A Puzzle Across Time

- Beyond the Hurrian Hymn: Other Ancient Musical Fragments

- The Human Drive for Music Across Ages

- Connecting to Our Ancient Past

- The Ever-Unfolding Story

- Frequently Asked Questions

The Elusive Quest for the Oldest Song

Finding the very first song is a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack that’s, you know, been scattered across millennia. Music from ancient times usually existed as oral traditions, passed from one person to another by listening and remembering. This means that, unlike, say, the Imago Mundi, which is the oldest known world map dating all the way back to the 6th century BCE, songs didn't often get written down. That map offers a unique glimpse into ancient perspectives, but a song just sort of floats away on the wind after it's sung. So, for a long, long time, we had no direct record of what these early melodies sounded like, which is a bit of a shame.

The challenge really comes down to the nature of sound itself. Sound waves are temporary; they don't leave fossils like ancient fungi, for example, which scientists struggled to confirm until discoveries that dated back some 400 million years. You see, without a way to record or write down music, it's virtually impossible to know what was sung or played thousands of years ago. We can find instruments, yes, but the specific tunes they played? That's another story entirely, and a much harder one to tell, naturally.

Archaeologists and historians rely on indirect clues: depictions of musicians, descriptions of musical events in ancient texts, or the discovery of actual instruments. But even with these clues, reconstructing a "song" in the way we understand it today is incredibly difficult. It's like trying to imagine a conversation from only seeing the speaker's mouth move, without any sound. That, you know, is a pretty tough task.

What Even Counts as a "Song"?

Before we can even talk about the oldest song, we really need to figure out what we mean by "song." Is it just any organized sound? Is it a melody with words? Does it need a specific structure, like verses and a chorus? Just as Visual Capitalist points out that using specific criteria, there is only one country with continuous democracy, defining "song" also requires specific criteria if we want to find the "oldest." If we consider any rhythmic vocalization or instrumental improvisation a "song," then music could be as old as humanity itself, which is, you know, a pretty broad definition.

However, if we're looking for something that resembles what we recognize as a structured composition—a melody with a clear pitch and rhythm, perhaps even with accompanying lyrics—then the pool of candidates shrinks considerably. This distinction is really important, because it moves us beyond just noise or simple sounds to something that required a degree of creative intent and, arguably, cultural transmission. So, what we're looking for is something more than just a hum, basically.

Many scholars suggest that a "song" implies a repeatable, recognizable musical piece, often with a communicative or artistic purpose. This means it's not just random sounds, but something intentionally crafted and performed. This focus on structure and intent helps narrow down the search, making it a bit more manageable, though still very challenging, you know.

Early Musical Instruments: The Precursors

While finding the oldest song is hard, discovering ancient musical instruments gives us a very real glimpse into humanity's musical past. These artifacts, found in archaeological sites, are tangible proof that our ancestors were making music tens of thousands of years ago. For instance, some of the oldest known instruments are flutes made from bird bone and mammoth ivory, discovered in caves in Germany. These date back over 40,000 years, which is, honestly, an incredibly long time.

These early flutes, with their carefully crafted finger holes, show that our ancient relatives understood pitch and melody. They weren't just making noise; they were creating deliberate, structured sounds. Imagine, if you will, the sounds these instruments produced echoing through prehistoric caves, perhaps during rituals or storytelling sessions. It's a truly powerful thought, really.

The existence of these instruments tells us that music was a part of human life long before any form of writing existed. It suggests that musical expression is deeply ingrained in our species, perhaps even playing a role in early communication or social bonding. So, while we don't have the "songs" they played, we certainly have the tools, and that's a pretty big step, as a matter of fact.

The Dawn of Notation: A Glimmer of Hope

The real breakthrough in identifying ancient songs comes with the invention of musical notation. This is when people started figuring out how to write down melodies, pitches, and rhythms, creating a permanent record that could be read and reproduced later. This development is incredibly significant because it means we no longer have to guess what ancient music sounded like; we can, in theory, actually play it. That, you know, is a really big deal for historians.

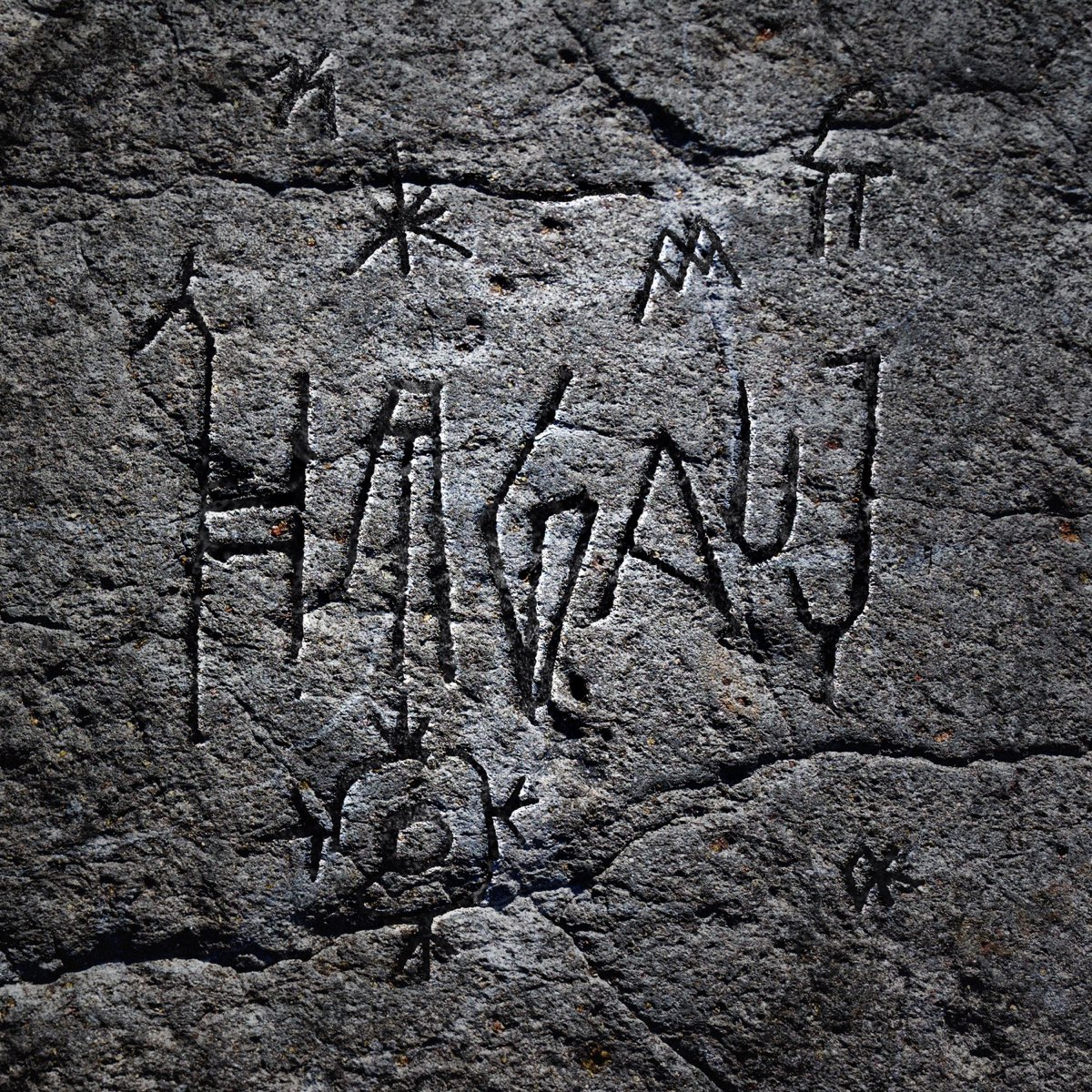

The earliest forms of musical notation are not like the sheet music we see today. They were often rudimentary, perhaps just symbols indicating melodic contours or specific pitches without precise rhythmic information. Think of it like early forms of writing, which were often pictographic or ideographic before evolving into more complex alphabets. It's a progression, basically, from simple hints to detailed instructions.

These early notations, though sometimes incomplete, offer tantalizing clues. They represent the first attempts to capture the ephemeral art of music on a durable medium. Without these pioneering efforts, the search for the oldest song would be almost entirely speculative. So, in a way, these ancient scribes were our first music preservers, which is pretty cool, you know.

The Hurrian Hymn No. 6: A Strong Contender

When people ask "What is the oldest song to ever exist?", one piece usually comes up: the Hurrian Hymn No. 6. This hymn was discovered on a clay tablet in the ancient city of Ugarit, located in modern-day Syria, back in the 1950s. It dates back to around 1400 BCE, making it, arguably, the oldest nearly complete piece of musical notation ever found. That, you know, is a seriously old tune.

The tablet contains both the lyrics, written in the Hurrian language, and detailed instructions for a singer and a lyre player. These instructions are written in a cuneiform script, which is a bit like reading a very old, very complex puzzle. Scholars have worked for decades to decipher these notes, trying to reconstruct the melody and understand the ancient musical system. It's a truly remarkable feat of historical detective work, really.

The Hurrian Hymn No. 6 is a religious piece, dedicated to Nikkal, the goddess of orchards. Its discovery was a monumental event because it offered direct insight into the structured music of a sophisticated Bronze Age civilization. It shows that people nearly 3,500 years ago had a complex understanding of music theory and composition. So, this isn't just a random scribble; it's a very intentional piece of art, as a matter of fact.

Interpreting Ancient Sounds: A Puzzle Across Time

Even with the Hurrian Hymn No. 6, reconstructing the exact sound is a challenging task. The notation isn't perfectly clear by modern standards, and there are different interpretations among scholars about how it should be played. It's a bit like trying to read a recipe from a very old cookbook where some of the measurements are missing or use terms we don't understand anymore. You know, you get the general idea, but the specifics are tricky.

Musicologists and archaeologists have used various methods to try and bring this ancient melody to life. They study the surviving instruments from the period, look at other ancient texts that describe musical practices, and apply their knowledge of historical tuning systems. The goal is to create a rendition that is as historically accurate as possible, given the limited information. It's a process of educated guesswork, basically, combined with serious academic rigor.

The interpretations often sound quite different from modern music, which is to be expected. They might feature microtonal intervals or unfamiliar scales, reflecting the unique musical sensibilities of the time. Listening to these reconstructions can be a truly humbling experience, allowing us to hear echoes of a distant past. It's a powerful reminder that music transcends time and culture, and that's a pretty cool thought, you know.

Beyond the Hurrian Hymn: Other Ancient Musical Fragments

While the Hurrian Hymn No. 6 often gets the spotlight, it's important to remember that it's just one piece of a much larger, fragmented puzzle. There are other ancient musical notations and fragments that offer glimpses into early music, even if they aren't as complete or as old. For example, some Sumerian texts from Mesopotamia, even older than the Hurrian hymn, contain what appear to be instructions for tuning musical instruments. This suggests a deep theoretical understanding of music even further back in time, which is, honestly, quite amazing.

Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings and artifacts also show various instruments and musical performances, though they don't provide actual notation. These visual records tell us that music was integral to religious ceremonies, celebrations, and daily life in ancient Egypt. So, while we don't have their songs, we know they were very musical people, basically.

The search for the "oldest song" is ongoing, and new discoveries could always change our current understanding. Just as the number of centenarians is growing fast, especially in Japan, and we're constantly learning more about human longevity, our knowledge of ancient music is always expanding. Each new artifact or deciphered text adds another piece to the vast mosaic of human history. It's a continuous process of discovery, you know.

The Human Drive for Music Across Ages

The pursuit of the oldest song isn't just about finding a historical curiosity; it's about understanding a fundamental aspect of human existence. Music is a universal language, a way we express emotions, tell stories, and connect with each other across cultures and time. From the earliest bone flutes to the Hurrian Hymn, the evidence suggests that humans have always had a deep, inherent need to create and experience music. That, you know, is a pretty powerful idea.

Think about how music impacts us today—it can stir our souls, bring back memories, or unite large groups of people. It's very likely that ancient music served similar purposes, perhaps even more profoundly in societies where other forms of communication or entertainment were limited. Music could have been a way to pass down knowledge, to strengthen communal bonds, or to communicate with the divine. It's a truly essential part of the human experience, really.

The fact that music has persisted for tens of thousands of years, evolving but never disappearing, speaks to its enduring power. It's a testament to our creativity, our emotional depth, and our desire to make sense of the world through sound. So, the oldest song isn't just a relic; it's a symbol of our shared humanity, as a matter of fact.

Connecting to Our Ancient Past

Discovering and interpreting ancient music allows us to connect with our distant ancestors in a very direct and emotional way. It's one thing to read about ancient civilizations, but it's quite another to hear a melody that might have been sung by someone thousands of years ago. It bridges the gap between then and now, offering a tangible link to lives lived long ago. That, you know, is a pretty special feeling.

This connection is similar to how we feel when we look at the Imago Mundi, the oldest known world map. It gives us a unique glimpse into ancient perspectives on Earth and the heavens, allowing us to see the world through their eyes. Similarly, ancient music lets us feel their joys, sorrows, and spiritual beliefs through their sounds. It's a way of experiencing history, not just reading about it, basically.

Understanding the oldest song, or at least the oldest fragments we have, helps us appreciate the long, rich history of human artistry. It shows that even in very early societies, people were capable of complex creative expression. It reminds us that our ancestors were not so different from us, possessing the same desires for beauty, meaning, and connection. So, in some respects, these ancient tunes are echoes of ourselves, you know.

The Ever-Unfolding Story

The quest for the oldest song is not a finished story. New archaeological discoveries are constantly being made, and new methods for interpreting ancient texts and artifacts are always being developed. Just as a new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and based on data from 20,000 individuals, concludes that birth order does matter, new data can always change our understanding of the past. There's always the possibility that an even older, more complete piece of music could be unearthed somewhere in the world, waiting to be deciphered. That, you know, is a pretty exciting thought.

The ongoing efforts to understand and preserve these ancient musical traditions are incredibly important. They help us to piece together the narrative of human culture and creativity, adding depth and richness to our understanding of where we come from. Each fragment, each instrument, each deciphered notation contributes to this grand story. It's a testament to human curiosity and perseverance, really.

So, while the Hurrian Hymn No. 6 currently holds the title as the oldest nearly complete song, the future might hold even more ancient surprises. The search continues, driven by our innate desire to connect with the sounds and stories of those who came before us. It's a journey through time, basically, guided by the whispers of ancient melodies, as a matter of fact.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the oldest musical instrument ever found?

The oldest musical instruments discovered so far are flutes made from bird bone and mammoth ivory. These were found in caves in Germany and date back to around 40,000 years ago. They show that early humans were capable of crafting tools to create specific musical pitches, which is pretty amazing, you know.

How do we know what ancient music sounded like?

Reconstructing ancient music is a bit like solving a complex puzzle. Scholars rely on several clues: surviving musical notation (like the Hurrian Hymn), archaeological finds of instruments, and descriptions of musical practices in ancient texts or art. They use this information to make educated guesses about scales, rhythms, and how instruments were played. It's a very careful process, basically.

Is the Hurrian Hymn No. 6 truly the oldest song?

The Hurrian Hymn No. 6 is widely considered the oldest nearly complete piece of musical notation with decipherable instructions for both lyrics and melody, dating to around 1400 BCE. While older musical fragments or instruments exist, this hymn is the most significant "song" we have found that we can actually try to play. So, it's a very strong contender for that title, you know. To learn more about ancient music on our site, and link to this page The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Related Resources:

Detail Author:

- Name : Shemar Zieme

- Username : ruecker.alexandre

- Email : dan.toy@gmail.com

- Birthdate : 1988-04-17

- Address : 6236 Ryan Lake Mitchellton, DC 11646

- Phone : (332) 466-4131

- Company : Vandervort, Rutherford and Tremblay

- Job : Molding Machine Operator

- Bio : Itaque qui fugit dignissimos minima aut pariatur corporis. Dolore cupiditate debitis ab vel nemo quos. Ea fuga autem excepturi ut optio. Vel atque dolores eos minus voluptate.

Socials

instagram:

- url : https://instagram.com/candelario_steuber

- username : candelario_steuber

- bio : Perspiciatis pariatur ullam consequatur vitae hic. Impedit velit totam autem nihil.

- followers : 2256

- following : 174

facebook:

- url : https://facebook.com/candelario_steuber

- username : candelario_steuber

- bio : Quasi ut voluptatem impedit est illo autem.

- followers : 123

- following : 1505

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@steuberc

- username : steuberc

- bio : Dolorum cupiditate sunt ut autem itaque dolor et.

- followers : 541

- following : 552

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/steuberc

- username : steuberc

- bio : Nostrum assumenda odit enim aut consequatur. Nostrum repellat perspiciatis id consequatur eveniet ratione nulla. Officiis beatae eos ipsam omnis.

- followers : 1591

- following : 2308

linkedin:

- url : https://linkedin.com/in/candelario.steuber

- username : candelario.steuber

- bio : Ipsum soluta laborum quibusdam adipisci sed.

- followers : 4796

- following : 1063